Uncommon Relationships or Connecting the Unconnected

One particular style of thought stands out for creative individuals, the ability to connect the unconnected by forcing relationships that enable them to see things to which others are blind.

Information from Cracking Creativity by Michael Michalko

"Da Vinci forced a relationship between the sound of a bell and a stone hitting water. This enabled him to make the connection that sound travels in waves.

Samuel Morse was stumped while trying to figure out how to produce a signal strong enough to be produced coast to coast. One day he saw horses being exchanged at a relay station and forced a connection between relay stations for horses and strong signals. The solution was to give the traveling signal periodic boosts of power.

Think of your mind as a bowl of ice cream with a flat surface. Imagine pouring hot water from a spoon on the ice cream and then tipping it so it runs off. After many repetitions of this process, the surfacce of the ice cream would be full of ruts. When information enters the mind, it flows, like water, into the preformed ruts. After a while, it takes only a small amount of information to activate an entire rut. This is the pattern-recognition and pattern-completion process of the brain. Even if much of the information is out of the rut, the mind will automatically correct and complete the information to select and activate a pattern.

When we sit down and try to will new ideas or solutions, we tend to keep coming up with the same old ideas. Information is activaing the same old ruts making the same old connections, producing the same old ideas over and over again. Or to put it another way, if you always think what you've always thought, you'll always get what you've always got.

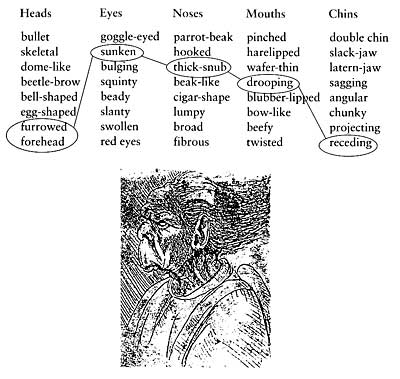

While the number of items in each category is relatively small, there are thousands of possible combinations of the listed features. The circled features indicate only one out of thousands of different groupings of features that could be used for an original grotesque head.

From his notebooks, it is clear that da Vinci used this strategy in his production of art and invention. He took the best parts of many beautiful faces, rather than create what he might consider to be a beautiful face and the end result, the Mona Lisa. It is intriguing to speculate that the Mona Lisa, probably the most admired portrait in the world, is a result of da Vinci combining the best parts of the most beautiful faces that he observed and systemized. Perhaps this is why admirers find so many different expressions in the mix of features on the face of the woman in the painting. It is especially interesting to consider this possibility in the light of the fact that there is so little agreement about the actual identity of the subject.

One can almost see Leonardo composing a matrix of elements (apostles, types of reactions, conditions, facial expressions, types of situations) and experimenting with their variations and combinations until he found the right configuration to create that once-in-a-lifetime master-piece-The Last Supper. Many other artists before him had made their own versions of Jesus Christ having his last meal with the twelve apostles. When Leonardo painted the picture, however, the scene came alive with new meaning that no one else was able to give nor has been able to give since.

Leonardo da Vinci would analyze the structure of a subject and then separate the major parameters (main category). He would then list attributes (variations) for each parameter and combine them. By coming up with different combinations of the variations of the parameters, he created new ideas.

Think of the parameters as card suits (hearts, spades, clubs, and diamonds) and the variations as the different cards within each suit. By experimenting with different combinations of the variations, you create new ideas.

To use da Vinci's attribute technique, follow these procedures:

1. Specify the challenge.

2. Separate the parameters of the challenge. The parameters are the fundamental framework of the challenge; the main guide lines. You choose the nature and the number of parameters that you wish to use in your box. A good question to ask yourself when selecting parameters is, "Would the challenge still exist without the parameter I'm considering adding to the box?"

3. Below each parameter (main areas), list as many variations (attributes) for the parameters as you wish. The complexity of the box is determined by the number of parameters and the number of variations used. The more variations and the more variety to the variations of each parameter, the more likely the box will contain a viable idea. For instance, a box with ten parameters, each of which has ten variations, produces ten billion combinations of the parameters and the variations.

4. When you are finished listing variations, make random runs through the parameters and the variations for the parameters, selecting one or more from each column, and assemble the combinations into entirely new forms. During this step, all of the combinations can be examined with respect to the challenge to be solved. If you are working with ten or more parameters, you may find it helpful to randomly examine the entire group, and then gradually restrict yourself to portions that appear to be particularly fruitful.

Let's look at an example. A carwash owner wanted to find an idea for a new market or new market extension. He analyzed the activity of "product washing" and decided to work with four parameters: method of washing, products washed, equipment used, and other products sold.

He listed the parameters and listed five variations for each parameter. He listed four parameters on top. Under each parameter he listed five variations for each parameter. He randomly chose one or more items from each parameter and connected them to form a new business.

| New Business Extension for Car Washes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method | Products Washed | Equipment Used | Products Sold | |

| 1. | full | cars | sprays | related products |

| 2. | self | trucks | conveyors | novelties |

| 3. | hand | houses | stalls | discount books |

| 4. | mobile | clothes | dryers | edible goods |

| 5. | combination | dogs | brushes | cigarettes |

Dogs-Self= dogs washing self

Stalls-dryers-brushes-sprays = same as car wash

New Business: The random combination of attributes ("self," "dogs," "brushes," "stalls," "sprayers," "dryers," "related products") inspired an idea for a new business. The new business he created was a self-service dog wash. The self-service dog wash has ramps leading to waist-high tubs where owners spray the dogs, scrub them with brushes provided by the wash, shampoo them, and blow-dry them. In addition to the wash, he also sells his own line of dog products, such as shampoos and conditioners. Pet owners now wash their dogs, while their cars are being washed in the full-service car wash.

Five alternatives for each parameter (main area)generates 3,125 possible different combinations. If only 10 percent prove useful, that would yield 312 new ideas. In theory, if you list the appropriate parameters and variations, you should have all of the possible combinations for a speciftied challenge. In practice, your parameters may be incomplete or a critical variation for a parameter may not have been described. When you feel this may be the case, you should reconsider the parameters you specified and adjust the parameters or the variations accordingly.

We tend to see the elements of our subject as one continual "whole" and do not see many of the relationships between the elements even the obvious ones. They become almost invisible because of the way we perceive things. Yet these relationships are often the links to our ideas. When you break down a subject into different parts and combine the parts in various ways, you restructure your perception of the subject. This perceptual restructuring leads to new insights, ideas, and new lines of speculation.

Gestalt psychologist Wolfgang Kohler demonstrated perception restructuring with animals. He would present an ape with a problem which bananas were displayed out of reach and could only be obtained by using techniques new in the ape's experience. For example, Kohler would give an ape boxes to play with for a few days. Then he would hang bananas from the ceiling out of the ape's reach. When he placed the boxes behind the ape, it would try all the familiar ways of reaching the fruit and fail. When he placed the boxes in front of the ape so they were visible, the ape would sit and think and suddenly have an insight and use the boxes to stand on to reach the bananas. What happened was that the visibility of the information restructured the ape’s perception. It suddenly saw the boxes not as playthings but as support to build a structure. It saw the relationship between the boxes and the bananas.

In the same way, when you combine and recombine information in different ways, you perceptually restructure the way you see the information. In addition, the greater the number of combinations you are able to generate, the more likely it is that some combination will serve as an associative link to ideas you could not come up with using your usual way of thinking (A, B, and D may become associated because each in some way is associated with C).

For example, the three words "surprise," "line," and "birthday" in combination serve as an associative link to the word "party." That is, "surprise party," "party line," and "birthday party." In the car wash example, an associative link was made from the information that was listed to the idea of a bird wash. The bird wash is a miniature clamp device that holds the bird securely in an upright stance so it can be gently washed and hosed (much like a carwash). It's designed to help workers cleanse birds who are damaged from oil spills at sea. It's expected to save thousands of birds that now expire from the rough handling during cleanup operations."